Nation Shall Look Unto Nation

8 May 2017 tbs.pm/12124

From the Television Annual for 1955, published by Odhams Press

The “speakerines of European TV visit Lime Grove and are here pictured with our Mary Malcolm (top). Already Jacqueline Joubert (centre), from France, was no stranger to the BBC television studios.

There is established a girdle of sight around Europe, so that men all the way from Scotland to Rome, and from Rome to Berlin, and from Berlin to Copenhagen, may now look at each other

And those musicians that shall play to you

Hang in the air a thousand leagues from hence;

And straight they shall be here.

Those are Shakespeare’s words. In 1954 British television viewers saw pigeons dipping over their native roofs in Rome on a sunny Sunday evening—about 1,300 leagues away! (The Celtic measure, a league, is computed at about three miles.) Carnival-time musicians in Montreux and Brussels and Siena, Danish country music from Copenhagen, and martial bands in Paris—all were heard and the players seen. So was the Pope, speaking from the Vatican.

On Whit Sunday, 1954, viewers saw the splendour of St. Peter’s and watched His Holiness Pope Pius XII as he said of television: “May this first international programme be a symbol of union between nations. Let the nations thus learn to know each other better… How many prejudices and how many barriers will thus fall! A new co-operation will be started. This is our hope.”

What His Holiness had to say, to eight viewing nations, provided a challenging and serious note. Like an inspiring, questing theme, it underlay the merry strains and gaiety of the other programmes seen. For it voiced the hope and the need of men, that some contribution to the peaceful union of the nations might in time be made by television.

The original motto of the British Broadcasting Corporation was “Nation shall speak peace unto nation.” But in 1938, when fortifications and not TV-links were the preoccupation of Europe, that motto was shelved. In its place appeared “Quaecunquee” to which some gave the innocuous meaning “What you will.” But the BBC maintained that it stood for the first word in the famous phrase “Whatsoever things are holy, whatsoever things are good…”

Today nation can look at nation — at any rate throughout Europe, and whatever the political situation, and however cold or hot this or that confined war. There is much to be done, and a long way to go before sight between nations can help to condition men’s minds towards political action which is more peace-making than war-fearing. But the beginning has been made. Certain men in eight countries, though they be specialized TV men, have in their action committed themselves to international TV. Millions of viewers, seeing the result, are witnesses of one small hope in a world of dashed hopes.

It may well be true that the TV link through Europe began as no more than a technical ambition pursued by engineers only keen to make the technical possibility come true. It may well be true that the TV programme-makers who became involved were also mainly ambitious to produce attractive and amusing pictures. It may well be true that viewers everywhere watched them only to seek a bit of novel excitement. But better this beginning than one made for hard political or idealogical purposes. Caxton did not print on paper in order to flood the people’s homes with newspaper leading articles and election manifestoes. He printed because he found the way to print. Marconi, so far as we know, burned not with international idealism, but with scientific urge, when he “wirelessed” across the Atlantic. Baird televised a wooden dummy’s head not out of love for his fellow men, but out of love for his scientific knowledge.

The fact that, in the main, international TV began by putting pretty pictures and amusement on the screens in no way reduces its potency now that it is in men’s hands. He would be foolish who passed himself off as wise enough to say it will never do more, and nobody can say how much it will do for good or evil. But we cannot deny that the more it is operated, and the more it is looked at, the more important it will become.

Long-range television is transmitted through a series of small relay transmitters erected on high points along the route. In the country town of Cassel, in France, one of these pieces of equipment was installed on the casino roof.

This truth already stirs among those working in it, however mundane their day-to-day ambitions for it. A German TV technician working on the first link-up told a BBC man working with him that, in the war, he was stationed in France at a blockhouse today used as one of the transmission centres for European TV. “Then it was a radar post, for trapping your flyers,” he said. “This that we do now is better, yes?”

It was “better” technically, and in its implications socially, when TV technicians first found the way to televise an event twenty-five miles away from the Alexandra Palace transmitter. The occasion was Ascot Races. A flippant occasion, in the view of some people; but it led to TV outside broadcasts from all over Britain as we know them today. The European link-up can be said to have started then. For the seed of the technical operation needed to take TV across a continent was planted between that English racecourse and Alexandra Palace. It was the technical means of carrying TV over hills and high obstacles.

Television can see far so long as its carrying waves are not obstructed. Heights interrupting the TV lines of sight have to be hopped over by means of midget relay transmitters sited on the higher points along the vision route. It was for Ascot Races that this technique was first crudely laid down. It was then developed considerably by the use of micro-wave links — series of midget transmitters, whose parasol-like “dishes” have now become the sign of TV operations right across Europe.

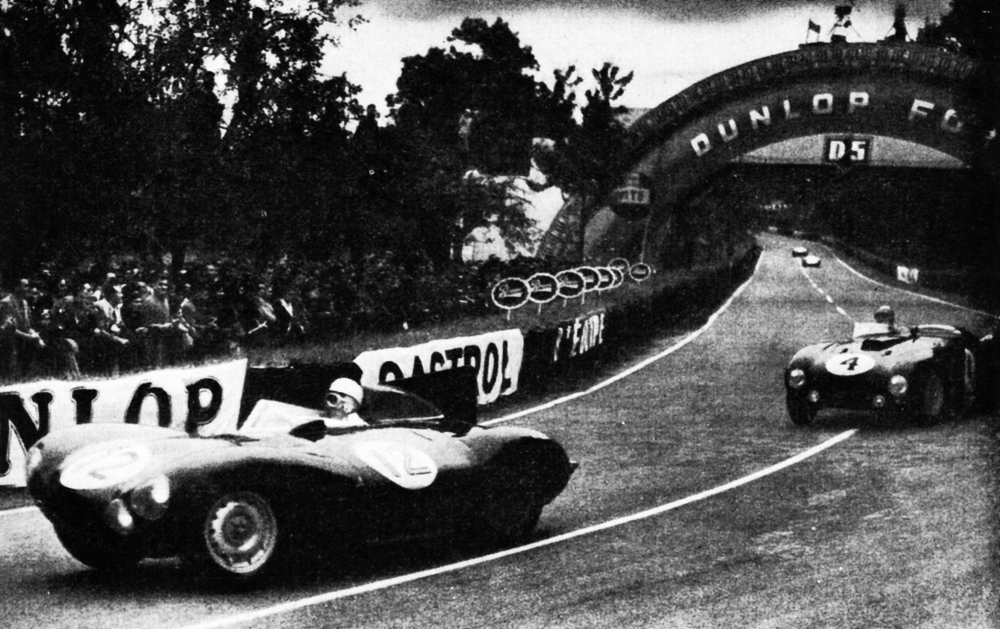

Exciting Sunday-afternoon viewing was provided in the relay from France of the Le Mans motor race. The Jaguar (No 12) driven by Stirling Moss and Peter Walker led the field at this point, the Tertre Rouge Curve.

Eighty of these relay points had to be installed, from Rome through Switzerland and France; and from France through Holland and Belgium to Germany and Denmark. They joined up forty-four European TV stations, permanent units of each TV system in eight countries. The network operated on two million pounds’ worth of British electronic equipment. It crossed the Alps, where relay transmitters stood on the peaks. Up 12,000 feet on the Jungfrau, the Swiss TV men installed a transmitter in the ice, and left it to operate itself automatically and even to keep itself warm! The cross-Channel lap in the link-up, which joined Britain to the Continent, used and improved on the experience gained in two previous BBC-France operations, in 1950 and 1952, when programmes were brought to Britain from Calais and Paris.

The link-up was reversible; it could bring to Britain, and it could take from Britain. The Continental countries watched Queen Elizabeth reviewing naval volunteers in London; saw athletics in Glasgow; horse-jumping at Richmond; and toured London by night. It was estimated that in Europe about a million and a quarter viewers watched the programmes. France and Italy are most advanced in TV, and provided between them about a million viewers. Western Germany, with half a dozen TV stations, added perhaps 200,000. The other probable audiences were: Holland 125,000; Switzerland 30,000; Belgium 15,000 and Denmark 10,000.

The World Cup football matches were a feature of the exchange of TV programmes between European countries. Here Uruguay’s Carlos Borges (second form right) scores in the match against England, televised from Basle.

These audiences are in direct proportion to the development of TV in the countries concerned. Indeed, the carnival televised from Montreux was only the third outside broadcast in the history of Swiss TV. Holland, Belgium and Denmark were also contributing to the link-up as “beginner” nations in TV operation.

A great part of the link-up was installed on a temporary basis in order to find out experimentally what were the potentialities of a permanent link through Europe. After the eighteen programmes which made up the experiment, each TV authority taking part expressed its desire to establish the link-up on a permanent basis as soon as possible. The most cautious estimate of engineers and programme men selects the winter of 1956 as the time when exchange of TV programmes throughout the European countries will be a normal part of TV broadcasting in general.

A tournament between standard bearers and horse-racing round the town square were shown in a programme from Siena in Italy.

Technical achievements apart, this result will call for a great deal of ingenuity, tolerance and broad-mindedness among the interested parties. The interested parties are not only the different national TV authorities. Every nation’s government will become more and more interested as aspects of the life it orders can be watched by other nations. The promoters of sports events will begin to wonder about the monetary advantage — or might it be disadvantage? — of showing their promotions so far beyond the boundaries of their arenas. The variety and theatre performers have already formulated the principle of bigger fees for showing their work by international TV.

The future of TV in the smaller European countries depends a great deal on the exchange of programme material, whether it be “live” or on film. For outside Paris and Berlin there are no great centres of performing talent for Europe’s TV authorities to draw on. Those two cities have not the very full resources of London. Some TV prophets see London becoming a kind of TV Hollywood to Europe. In London would be made TV films for European countries, and later, perhaps, live TV programmes in the required languages.

A summer evening on the Rhine was captured in a relay from West Germany. With Drachenfels castle across the river, viewers saw scenes in a holiday camp run by young people and watched the varied river traffic pass by.

Finding the financial resources for doing this; devising equitable fees for those doing it; and settling problems of distribution, and even of Customs duty on TV equipment, will call for international agreements in no way easy to come by.

But the first step towards world-encircling TV has been taken. To the east the Iron Curtain bars the way; to the west, the expanse of the Atlantic, still technically unspanable by TV. No one can predict in which direction TV will take its second roaming step—or whether, indeed, the sally will be made by America towards us. Futuristic talk of aircraft hovering over the Atlantic, whilst being used as TV-link stations, is discounted in knowledgeable quarters. The only serious thought being given to transatlantic TV in the United States centres on a theoretical route via Newfoundland, Greenland and Iceland, which it would seem requires a vast cable installation of immense cost.

You Say

1 response to this article

Paul Mason wrote 8 May 2017 at 12:20 pm

One unpleasant side effect of all these works was the Eurovision Song Contest!

Your comment

Enter it below